- English Major

- English Major with Teaching Certification

- English Minor

- Creative Writing Minor

- Capstone Program in Creative Writing

- Capstone Program in Research

- Journalism

- English in Action

- Advising Information

- English Department Writing Program

-

- First-year Writing Requirement

- Courses

- Policies & Procedures

- Director's Note

- Writing Resources

- Contacts

- Teaching of Writing

- 2024 Commencement

- Study Abroad

A Passion for the Teaching of Writing

Laura Aull

—Graduate Student Instructor

Two things about teaching I look most forward to are getting to know students and working with them to see more deeply into the (often hidden) expectations that shape writing and literature. Part of that endeavor includes exploring how our cultures—academic, national, social, global— influence the production and consumption of texts. I see my courses as a collective endeavor to greater critical consciousness of such processes that we then bring to bear on all we read and write and witness.

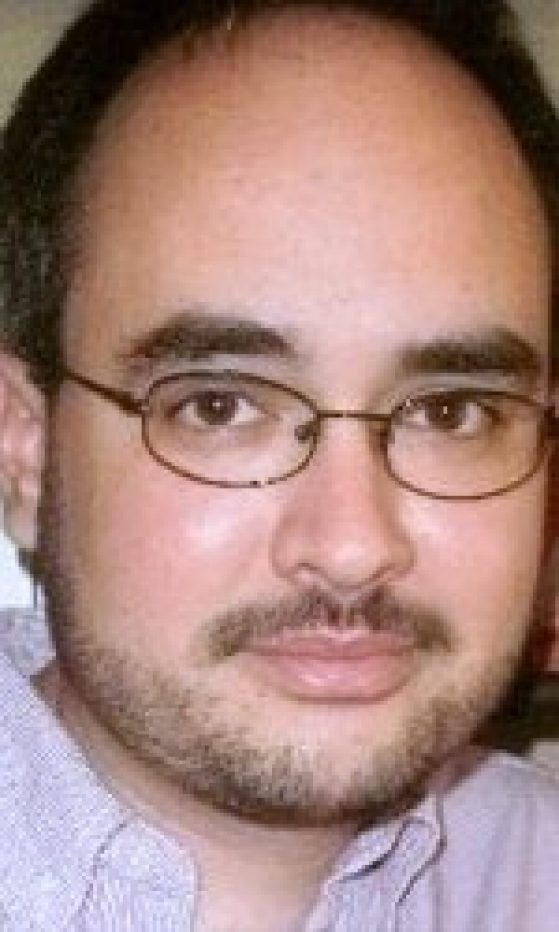

Paul Barron

Paul Barron

—Lecturer, Sweetland Writing Center

I try to help students make connections to what they have already accomplished as writers and to prepare them for the way forward. I want them to develop a collection of skills and strategies they can adapt to any writing situation, whether academic, professional, or creative. But more than this, I want my courses to offer a way for students to improve themselves in a deeper way. We have the right to speak, but since we don?t have the right to be heard, we have to take responsibility for how we communicate. As writers, our job is to interest readers, but also to develop our knowledge of and faith in ourselves and, always, to remain open to discovery.

Jeremiah Chamberlin

Jeremiah Chamberlin

—Lecturer

My primary goal in the classroom is to foster a desire for questioning and inquisitiveness in each of my students. Intellectual curiosity is a lifelong endeavor, one that enriches our lives long after we leave the University. And regardless of an individual’s career path, creativity and critical thinking are invaluable skills to possess. This is why I teach my students that the very act of writing is a process of learning and exploration. As Don DeLillo says: "Writing is a concentrated form of thinking. I don’t know what I think about certain subjects, even today, until I sit down and try to write about them."

However, intellectual curiosity alone does not guarantee successful writing. Writing needs to matter beyond the personal. In each of my courses—whether I’m teaching creative writing, essay writing, or argumentative writing—I ask my students to interrogate how their work speaks to broader social and cultural issues. In short, why it matters.

This is what I love most about teaching: showing students that writing is a dynamic and individual process. It is not about saying the right thing or finding the right answer. Rather, it is about asking questions and finding new ways of seeing the world. By doing so my students not only develop academic skills crucial to success in our University community, but they also find ways to better express and understand themselves.

Bethany Davilla

Bethany Davilla

—Graduate Student Instructor

As someone who loves both writing and teaching, I enjoy helping my students become better writers. I work hard to create a safe and engaging space for students to experiment with writing. One way I encourage this experimentation is by teaching genre. My students learn how to analyze conventions and audience expectations, and they have the opportunity to mix genres and consider the effect. Ultimately, I aim to help my students become confident, capable, and conscientious writers.

Nate Mills

Nate Mills

—Graduate Student Instructor

The first thing I try to impress upon my students is that the college classroom is often the one place where they will be asked what they think about any given subject or problem. It is their perspectives that their teachers and peers want to hear and evaluate. I tell them that this is both an immense challenge and an exciting opportunity, the chance for them to explore their own intellectual investments as they communicate their ideas in writing that meets the academy’s high standards for intellectual complexity. I introduce students to practices of reading, analysis, and argument in order to equip them for the arduous and rewarding task of figuring out what they think, why they think it, and why their peers should pay attention to it. This process of intellectual exchange is, in my view, the real heart of a liberal arts education and a critically important experience for undergraduates of all majors and in all career paths.

Fritz Swanson

Fritz Swanson

—Lecturer

When students come to the University of Michigan, they are hungry to move beyond high school, to change from knowledge receivers into knowledge makers. My single goal is to show students the basic outline of that process, which is the foundation of academic inquiry. A broad outline can set the parameters of what is knowable. It’s utility comes when, over time, students are able to fit in all of the disparate activities they do at the University into one system, one process.

First-year composition is one of my favorite classes because students at this moment in their education are most open to building broad models.